I went to a

Chroma reading last night at Waterstones on Oxford Street (

Chroma is a literary journal in which my poems have appeared) to watch my writer-pal Brynn read his winning story,

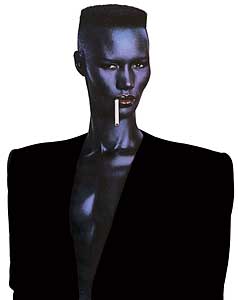

Spawn of the Regime. While he was chatting to Louise Hercules, this month's

Chroma cover-girl, I sat down with a mince-pie and a glass of water and looked around at the crowd. Straight away, I found my eyes drawn to a familiar face on the other side of the room. It was a face I will never forget, probably because it's so closely associated with a time in my life in which I was happiest. "Caroline," I said, raising my voice above the crowd. "I knew it was you!" she said.

The most interesting thing about my friendship with Caroline (a friend of mine at primary school) was more the backdrop over which our friendship played out - the fact that the school we attended was such a special place - the stuff of dreams, really, or of Harry Potter as Caroline said last night. In the heart of the English countryside,

Tockington Manor was surrounded by acres of grounds in which we could lose ourselves for hours: sometimes we'd read together quietly in the woods; sometimes we'd venture far into the trees and sit on a moss-covered rock that we called, oddly, 'the quarry'; sometimes we'd tell stories and fantasize we had magic powers; at all times, though, we were surrounded by nature, by rabbits running through the vast fields, by enormous oak-trees that swept their leaves across the green, and deep woods that rustled their leaves, and pear trees that grew against the old stone walls. It was as if the headmaster and his wife believed in the Romantic ideal that contact with nature is crucial to the instruction of sensitive beings - and I am grateful to my mother and the Toveys for allowing my soul to be attuned, at least for a time, to the natural rhythm of the universe. The experience was character-building and continues to influence my creativity today.

When I think about it now, and realise how far the lives of Caroline and myself have diverged, and how good that time was and how it's now gone, and the years of alcoholism that followed, I feel sad; until I think that other children are enjoying today what I enjoyed all that time ago. This is an extract from a poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in which he writes about what I'm trying to say more lucidly than I ever could. It's called 'Frost At Midnight' and it's addressed to his son, Hartley:

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the interspersed vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought!

My babe so beautiful! it thrills my heart

With tender gladness, thus to look at thee,

And think that thou shall learn far other lore,

And in far other scenes! For I was reared

In the great city, pent 'mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

Great universal Teacher! he shall mould

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee,

Whether the summer clothe the general earth

With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing

Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch

Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch

Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.